Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news about fascinating discoveries, scientific breakthroughs and more.

CNN

—

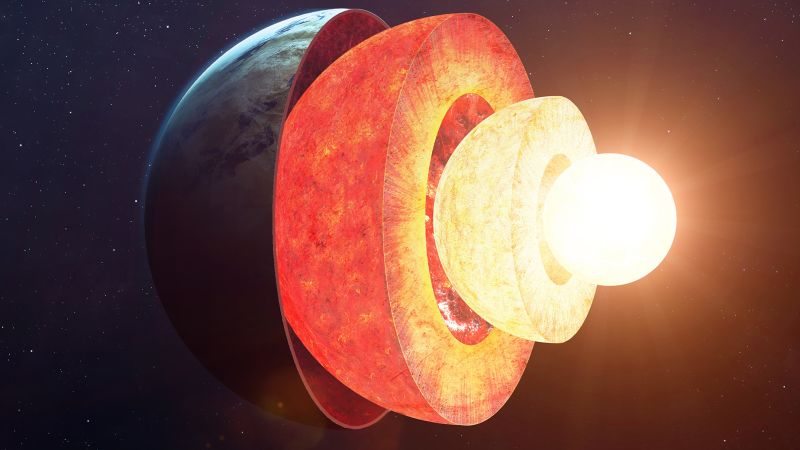

Deep inside the Earth is a solid metal ball that spins independently of our rotating planet, a top-spinning inside a giant dome, shrouded in mystery.

This inner core has fascinated researchers since it was discovered by Danish seismologist Inge Lehmann in 1936, and how it moves—its rotational speed and direction—has been at the center of a decades-long debate. Growing evidence suggests that the core’s rotation has changed dramatically in recent years, but scientists are divided on exactly what’s happening — and what that means.

Part of the problem is that it is impossible to directly observe or model the Earth’s deep interior. Seismologists have gathered information about the movement of the inner core by studying how the waves of large earthquakes that ping the region behave. Variations between waves of similar strength passing through the core at different times enabled scientists to measure changes in the position of the inner core and calculate its rotation.

“Divergent rotation of the inner core was proposed as a phenomenon in the 1970s and 80s, but it was only in the 90s that seismic evidence was published,” said Dr Lauren Waszek, a senior lecturer in James Cook’s Department of Physical Sciences. University in Australia.

But researchers debated how to interpret these findings, “primarily because of the challenge of making detailed observations of the inner core, due to its remoteness and limited amount of data,” Waszek said. As a result, “studies that followed in the years and decades that followed disagreed on the rotation rate, and also disagreed on its direction with respect to crust,” he added. Some analyzes have proposed that the core does not rotate at all.

A promising model Proposed in 2023 He described an inner core that had rotated faster than Earth in the past, but was now rotating more slowly. For a while, the spin of the core matched the spin of the Earth, scientists said. After that, it slows down even more until the core moves backwards relative to the liquid layers around it.

At the time, some experts warned that more data were needed to strengthen this conclusion, and now another group of scientists has provided new evidence for this hypothesis about the rotation rate of the inner core. The research was published June 12 in the journal Nature In addition to confirming a major recession, 2023 supports the proposition that this core slowdown is part of a multi-decade cycle of slowing and accelerating.

Playday/iStockphoto/Getty Images

Scientists study the inner core to learn how Earth’s deep interior is formed and how activity connects to all of the planet’s surface layers.

The new findings confirm that changes in cycle speed follow a 70-year cycle, said the study co-author. Dr. John VidalDornsife Professor of Earth Sciences in the College of Letters, Arts and Sciences at the University of Southern California.

“We’ve been arguing about this for 20 years, and I think this is pushing it,” Vidal said. “I think we’re done with the debate about whether the inner core is moving and what its pattern has been over the last two decades.”

But not everyone believes the matter is settled, and how the deceleration of the inner core might affect our planet is still an open question — although some experts say the Earth’s magnetic field might come into play.

Buried about 3,220 miles (5,180 kilometers) deep inside the Earth, the solid metallic inner core is surrounded by a liquid metallic outer core. The inner core is composed mostly of iron and nickel, and is estimated to be as hot as the Sun’s surface—about 9,800 degrees Fahrenheit (5,400 degrees Celsius).

Earth’s magnetic field pulls on this solid ball of hot metal, causing it to spin. At the same time, the gravity and flow of the liquid outer core and mantle pulls it into the core. Over decades, the push and pull of these forces cause variations in the center’s rotational speed, Videl said.

The sloshing of metal-rich fluid in the outer core creates electricity that powers Earth’s magnetic field, protecting our planet from deadly solar radiation. Although the direct influence of the inner core on the magnetic field is unknown, scientists have previously reported In 2023 A slowly rotating core can affect it and partially shorten the length of a day.

When scientists try to “see” across the planet, they typically observe two types of seismic waves: stress waves, or B waves, and shear waves, or S waves. B waves move through all kinds of materials; S waves can only travel through solids or very viscous liquids US Geological Survey.

In the 1880s seismologists noted that the S waves generated by earthquakes did not travel across the Earth, so they concluded that the Earth’s core had melted. But some B waves, after passing through the Earth’s core, emerge in unexpected places — the “shadow zone,” as Lehman calls it. called it – Creating inexplicable contradictions. Based on data from a massive earthquake in New Zealand in 1929, Lehmann first suggested that deviant P waves could interact with a solid inner core in a fluid outer core.

By tracking seismic waves from earthquakes that have passed through Earth’s inner core on similar paths since 1964, the authors of the 2023 study found that the vortex follows a 70-year cycle. By the 1970s, the inner core was rotating slightly faster than the planet. It slowed down in 2008, and from 2008 to 2023 began to move slightly in the opposite direction relative to the horizon.

For the new study, Vidal and his co-authors observed the seismic waves generated by earthquakes in the same locations at different times. They found 121 examples of such earthquakes between 1991 and 2023 in the South Sandwich Islands, an archipelago of volcanic islands in the Atlantic Ocean east of the southern tip of South America. The researchers also observed core-penetrating shock waves from Soviet nuclear tests conducted between 1971 and 1974.

As the core rotates, it affects the arrival time of the wave, Videl said. Comparing the time the seismic signals hit the epicenter revealed changes in epicenter rotation over time, confirming a 70-year rotation cycle. According to the researchers’ calculations, the core is ready to start accelerating again.

Compared to the center’s other seismological surveys, which measure individual earthquakes as they pass through the center — regardless of when they occur — using only linked earthquakes reduces the amount of usable data, “making the method more challenging,” Waszek said. However, doing so allowed the scientists to measure changes in the core circulation with greater precision, Videl says. If his team’s model is correct, the core rotation will begin to accelerate again in about five to 10 years.

Seismograms show that during its 70-year cycle, the center’s spin slows and accelerates at different rates, “which would require an explanation,” Videl said. One possibility is that the metal inner core is not as solid as expected. If it deforms as it rotates, it could affect the symmetry of its rotational speed, he said.

The team’s calculations also suggest that the core has different rotation rates for forward and backward motion, which adds “an interesting contribution to the conversation,” Waszek said.

But the depth and inaccessibility of the inner core mean there are uncertainties, he added. As for whether or not the debate about central rotation is truly over, Waszek said, “We need more data and improved interdisciplinary tools to investigate this further.”

Changes in the central circulation — although they can be observed and measured — are all invisible to people on Earth’s surface, Videl said. While the core rotates slowly, the mantle accelerates. This change causes the Earth to spin faster, and the length of a day decreases. But such cyclic changes are only a thousandth of a second in day length, he said.

“As for that effect on a person’s lifetime?” he said. “I can’t imagine it means that much.”

Scientists study the inner core to learn how Earth’s deep interior formed and how activity connects all the planet’s surface layers. The mysterious region where the liquid outer core covers the solid inner core is particularly interesting, Videl added. As a place where fluid and solid meet, this boundary is “rich with potential for activity,” as is the core-mantle boundary and the boundary between crust and crust.

“There could be volcanoes at our inner core boundary, for example, where solid and liquid meet and move,” he said.

Since the spin of the inner core affects the motion in the outer core, it is thought that the inner core spin helps power the Earth’s magnetic field, although further research is needed to unravel its precise role. Much remains to be learned about the overall structure of the inner core, Vasek said.

“New and upcoming methods will be central to answering current questions about Earth’s inner core, including rotation.”

Mindy Weisberger is a science writer and media producer whose work has appeared in Live Science, Scientific American, and How It Works magazine.